The price of a work of art is established by one factor – what someone is willing to pay! I have had this discussion with artists who feel devalued by such a definition, but all products and services are treated equally in the marketplace. Art is not immune to “supply and demand”.

When only a few people are attracted to a painting the value isn’t diminished to the person who perceives some personal relevance. At auction, the under-bidder did not value the object any less than the winner of the auction. He just chose to set the amount he was willing to spend at one bid lower than the successful bidder. One cannot explain after examining the auction results of a specific artist why one object sold for $35 and another for $35,000? Those differentials exist for most artists though. Let me try to explain.

When we choose to purchase a painting we normally evaluate its condition, look for a signature that is consistent with other validated work, match the subject of the painting with the genre for which the artist is identified most closely, and judge the size of the painting with respect to the subject depicted (i.e. is it large enough to provide enough detail) and the size of the space where we wish to hang it. Even the previous owners may significantly effect the value. Other factors like age of the painting, nationality of the artist, the medium used by the artist (oil, watercolor, pencil, pastels, charcoal, etching, sculpture), and whether it is a single rendering or one of multiple copies – sometimes artists painted the same subject numerous times and others used material such as wood blocks and metal plates to print numerous copies in black and white or in color. All are classified as “original” art because they were constructed by the hand of an individual artist and not the photographic representation which likely were produced in hundreds or thousands.

For some people, a tattered piece of paper with a drawing by an imminent painter is worth a small fortune. For others, a spot of foxing, a crease in the paper, or a water stain renders the art undesirable. One collector may wish to buy only the work of female artists, while another chooses a single subject or period – considering the identity of the artist to be insignificant.

While all the factors mentioned are important considerations for determining value, they are subsidiary to quality. The maxim “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure” speaks to the difficulty of identifying quality. There are essential elements in drawing and painting – and in all art – that must be present to the trained eye, but there are exceptions. The work of artists like Grandma Moses, for example. Primitive art is a specialized interest but does not meet the constructive requirements of purists. Quality goes far beyond technical mastery, however!

It should be obvious that with so many variables, art bearing the same signature could sell for $35 or $35,000. The $35 painting was likely rejected by most bidders as a fake or a copy by another artist. Also, the condition may have been so poor as to render it unattractive and beyond restoration.

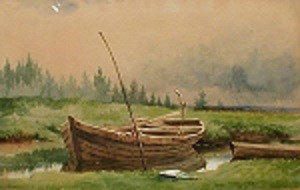

My collection was begun without the benefit of any formal study. If I liked it, I bought it – if I had the money! I discovered, though, that I had a “good eye” for quality, however that word is defined. Finally, though, my success in buying was dependent on how many other “good eyes” were viewing the art that appealed to me. With my financial constraints, I focused my buying on what I have described as minor works by major artists and major works of minor artists. The best example of the former is a watercolor drawing by a Scottish artist whose paintings of Irish peasants brought remarkable success to the artist in the early and mid-19th century. My watercolor is of a rowing boat in a backwater with no figures. It is clearly signed, inscribed, and dated 1851 in the hand of Erskine Nicol!

There can be no question about the attribution, quality, or condition. Nevertheless, it will sell for far less than an Irish cottage scene. In every way except the subject, this is a highly desirable painting. One that will not be sold in my lifetime but when it is the purchase price will be a small, compared with Erskine Nicol’s paintings of Irish peasants. It should be noted, though, that this watercolor would be happily accepted by Sotheby’s for one of their feature art sales!

I have many examples of major work by minor artists – too numerous to choose the best example but I will illustrate with one of them. An Edinburgh artist working in the first half of the 20th century produced a large volume of watercolors, pencil, and pen and ink drawings in a variety of genres. I was fortunate to buy a few of them and his watercolor titled Windy Day on the Cornish Coast is reminiscent of Turner’s best during his “modern” period.

William Miller is referenced in only one book as far as I am aware, and his career seems to have halted prematurely (around the time of WWII). He has also been eclipsed by William Miller 1796-1882 and and William Miller Frazer 1864-1961. Had his career been sustained it is certainly possible he would have demanded the same respect as the other two William Millers! The failure of an artist to become commercially successful, whatever the reason, is not a measure of his artistic merit!

Finally, when considering the purchase of art, one must consider the cost of presentation – frame or mat, hanging or storage in a box or drawer. And, not to be discounted is the cost of delivery from the point of purchase to the buyer’s home or business.

Let us look at the latter consideration first. The cost of packing and shipping a painting represents a significant amount of the total acquisition cost. Delivered to a contiguous state a small painting, framed or unframed, is likely to cost a minimum of $25, a medium painting $50, and a large painting up to $200. My practice is not to ship anything that will add more than $200 to the price of the painting – my most expensive item being $9500. For these larger, more expensive items, I offer to sell for pick up only. Shipment to overseas destinations will be determined on an individual basis.

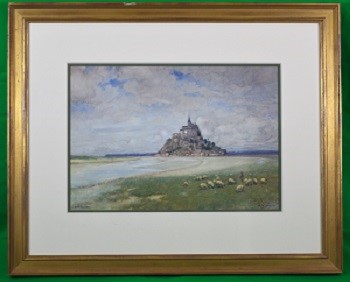

The presentation of a painting is vital to its full enjoyment and essential for its preservation. The art should be professionally matted and/or framed using conservation materials. That isn’t cheap! My watercolor of Mont St. Michel by Scottish painter Peter Alexander Hay was purchased for $380 but the matting and frame added another $400 to the total cost.

My price of $995 reflected all overhead expenses and a small profit. After dropping the painting and putting a dent in the upper edge of the molding, I have had to reduce the price by $200 with the expectation that I will lose money when this painting is sold. The quality of the painting and desirability of the subject justified the re-framing cost, however, and was a sound investment. Gone is the recovery of overheads and profit for this watercolor, but that’s part of the cost of doing business.

I suppose I have said enough about the pricing of paintings except to reiterate that a painting is worth what one is willing to pay. Guidelines for what a painting should cost in the art market are relevant, but my advice is that when one sees a work of art they like and the price seems reasonable, they should buy it. The price may never be lower and in time it is more likely to increase. My failures to buy an art object loom far more in my mind than any regrets for spending too much!

Enjoy a browse through an eclectic collection. If you like something, make an offer! Estimates are a starting point for discussion. Share your interests and impressions with an email. Also, bookmark to review new listings.